Which site would you like to visit?

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.

Looking for currently available vinegars? Click to Jump to the List

For at least a millennium, Italy’s province of Emilia-Romagna has been the source of one of nature’s greatest, and rarest, gastronomic gifts, Balsamico.

Until the 1970’s, Balsamico was never sold and was virtually never seen outside of its home—or if it did appear, it was in the guise of an imposter that bore no resemblance to the real thing. Even today, few Americans—including many among our culinary elite—have ever experienced the pleasures of real Balsamico.

Balsamico Tradizionale, as this nectar is now officially known, is luxuriously sweet and thick in texture, with a color that approaches ebony black. Its bouquet is one of the most intense imaginable, rivaling white truffles in its sybaritic power. And its concentration is so intense that just a few drops can transform a dish.

Balsamico Tradizionale is produced in and around two cities of Emilia-Romagna: Modena and Reggio-Emilia. It differs from nearly all other vinegars in that it is not made from wine or another fermented juice; it is made according to an ancient local recipe, from the juice of fresh, crushed grapes cooked down to a fraction of its original volume.

It is then aged in small casks for at least 12 years—and often for 25 to 30 years or more—under the eaves of local houses, in rooms called acetaie. It is an incredibly costly process, requiring a half ton of grapes to produce a gallon of 25-year-old Balsamico.

The cities of Modena and Reggio-Emilia both produce Balsamico Tradizionale under strict regulations. However, we have chosen to focus on Modena, considered by many to produce the finest Balsamicos.

With its amazing concentration and complexity, there are infinite uses for Balsamico Tradizionale. It can be drizzled over aged Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, meats, fish, vegetables, fresh berries and melon, and ice cream—adding new dimensions to their flavors and aromas.

Balsamico Tradizionale is very rare. As recently as 1991, less than 300 gallons were made in the entire Modena region. Today, production is somewhat greater; but still only a few specialty retailers in the United States have it available, and seldom more than one or two examples from a single producer are offered.

When we first tasted true artisanal Balsamico on a visit to Italy in 1993, we were struck by the parallels with great wine: the mesmerizing color, the compelling nuances of bouquet and the subtleties of taste.

But the real test came when we had the chance to compare more than two dozen different Balsamicos from a dozen producers. For all of their diversity and complexity—and the amazing level of quality—we could just as easily have been tasting great wines.

For years, our Balsamico offerings have paralleled what we’ve done for Tuscan extra-virgin olive oil: assemble the finest selection available anywhere, and offer them with the greatest depth of information, and at the lowest prices, possible.

The recorded history of Balsamico dates back at least to 1046, when Reggio-Emilia’s Marquis of Canossa gave the Roman Emperor Enrico III a silver cask of his famed vinegar. Fifty years later, a product called balsamo, or balm, appeared—praised not only for its medical benefits, but also for its powers as an aphrodisiac.

A consorzio was formed to keep the production of this special vinegar a secret. Even today, to tenaciously hold a secret in Italian is tenere il segreto dell’aceto (to keep the secret of the vinegar). During the reign of the powerful Duchy of Este—from the 1500’s to the early 1800’s—Balsamico came into its own.

The Este family built a massive acetaia for their own use, lavishing their aceto del duca Balsamico on rulers all across Europe. Over the centuries the legend of Balsamico grew.

In The Splendid Table, Lynn Rossetto Kasper writes that during the plague of 1630, the Duke of Modena refused to leave his castle without an open jug of balsamico purifying the air in his carriage. Lucrezia Borgia touted its value for the discomforts of childbirth, while the composer Rossini, among many others, advocated its use as an emotional restorative. Even today, balsamic makers leave an open cask in their homes, freshening the air and warding off sickness, while carrying little flasks with them everywhere.

Eventually, the secrets of making Balsamico leaked out, allowing dozens of families around Modena to create acetaie in their own attics. And while true Balsamico was essentially unavailable commercially, its fame spread, acquiring a mythic reputation among cooks.

The big food companies in and around Modena responded by creating a range of products called “Balsamic Vinegar of Modena” selling for as little as $2 or $3 a bottle. These were cheap wine vinegars to which was added caramel and, occasionally, cooked grape juice. On the palate, they bore no resemblance to true Balsamico.

In the 1960’s, the small artisanal producers tried to stop this abuse of the Balsamico name. They succeeded in having the government require that “Balsamic Vinegar of Modena” be at least 10 years old. However, the government allowed an unspecified amount of younger vinegar to be added, with no prohibition against the use of caramel. In effect, little changed.

By the late 1970’s, having finally begun to market their Balsamico, the artisan producers banded together to form the Consorzio di Produttori Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena. They seized on the word “tradizionale” to differentiate their product from the industrial vinegars and required all members to make their Balsamico according to strict guidelines. The rules stipulated that:

The Balsamico could only be made from the pure juice of any of five grape varieties—Trebbiano, Lambrusco, Occhio di Gatto, Berzemino and Spergola—cooked down to concentrate its richness. No caramel, flavorings or coloring may be added.

The Balsamico must be aged for a minimum of 12 years in a battery containing at least 3 casks.

When the Balsamico is ready to be sold, the entire amount is sent to the Consorzio for blind tasting by a panel of experts. The amounts submitted are usually miniscule (often just a gallon or two).

The Balsamicos are scored on a scale of up to 400 points, evaluating for density, color, clarity, finesse, intensity, flavor, aroma, harmony and acidity. The minimum passing score is 229 for a 12-year-old and 255 for a 25-year-old “extravecchio” (very old). While more than half are rejected and sent back for further aging, those that pass are bottled and sealed by the Consorzio.

Of all the factors influencing the quality and character of a Balsamico, the most important are the twelve or more years in the acetaia (pronounced “ah cheh tie ya”). It is argued that Modena produces the greatest Balsamico because of the wide swings of its climate, with cold winters and hundred-degree days in summer. Efforts to make Balsamico in Bologna just a few miles away have been notable failures.

The truest expression of the Balsamico makers’ art is in the barrel-aging. All Balsamico is aged in a series of progressively smaller casks which, as a group, are known as a battery. Though a battery must contain a minimum of three barrels, most consist of six or seven casks of varying woods: oak, chestnut, acacia, ash, cherry, mulberry and juniper, each imparting a unique flavor.

The most distinctive may be cherry, which adds sweetness, and juniper which gives an intensely cedary flavor. But because it is illegal in Italy to cut down juniper trees, juniper casks are today the rarest; many acetaie just have one or two juniper barrels which are used for blending.

The older the barrel the more prized it is. Many acetaie have centuries-old barrels, handed down from earlier generations. Often, if an old barrel begins to leak badly, a new barrel is built around it, allowing the old staves to continue to work their magic.

Because air contact is essential, the barrels are only about 3/4 filled, and the tops of the casks have rectangular openings which are never sealed. While it is most typical to lay a piece of cloth over the opening, a loose-fitting stone is occasionally used. When young, the vinegar’s aroma is so acidic that it corrodes the stone, allowing minerals to precipitate into the cask.

When visiting an acetaia it is fascinating to witness how Balsamico ages, becoming more and more intense and thick on the palate, while its bouquet mellows and deepens. Putting your nose over the opening of a cask of young Balsamico can be excruciating, as the intensely acidic bite of the aroma invades every pore of your nose.

Inhaling from a barrel of 20 or 25-year-old Balsamico is an altogether different experience: the heady aroma hasn’t a trace of harshness. This is one of the miracles of aged Balsamico.

Regardless the number of casks, or the types of woods chosen, the function of the battery is always the same: the first barrel in the series is the largest and contains the youngest vinegar; the last is the smallest and contains the oldest.

When deemed ready for sale, a portion of the Balsamico in the last barrel is withdrawn and put into a jug to be taken to the Consorzio for evaluation. If the Balsamico passes and is sold, the space in the final barrel will be filled from the preceding barrel in the battery, and so on down the line. If the Balsamico fails the examination, it will be returned to the battery for additional aging.

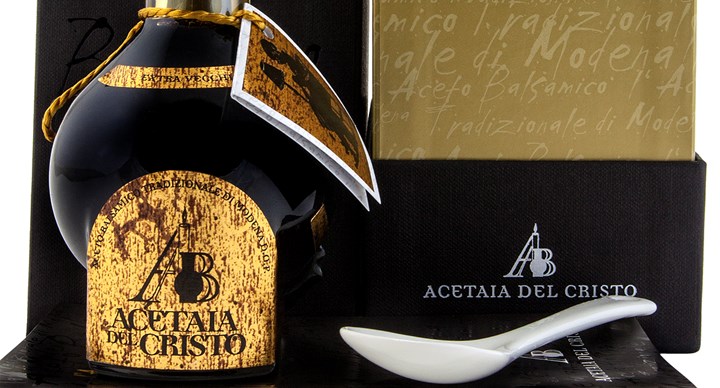

In “The Balsamico Wars” (see History above) the Consorzio has distanced itself from its imitators in two ways: (1) adopting the word “tradizionale” for its labels (only they can legally use this word) and (2) creating a distinctive bottle for the exclusive use of Consorzio-approved Balsamico.

For their signature bottle, in 1988 the Consorzio called on Milan’s Giorgetto Giugiaro, one of the most influential Italian designers of the twentieth century. A short list of his works includes the classic Nikon F camera and a number of important Bugatti cars. Giugiaro’s distinctive design for the Balsamico Tradizionale bottle evokes elements from Balsamico’s long history.

In 1999, Lidia Bastianich, the owner of New York’s famed Felidia restaurant, offered her secret to using Balsamico: “A mere drop, certainly no more than a drizzle, is all you’ll need. It’s best very lightly sprinkled over wild strawberries or atop a plain risotto. A single drop, though is absolute perfection with Parmigiano.”

There are few foods on the planet with Balsamico’s versatility. It’s at home on meat, fish, cheese, vegetables, pasta, eggs, fruit and ice cream. And you can sip it. Balsamico doesn’t just complement foods; it elevates them to a higher plane of gustatory excitement.

Like truffles, Balsamico excels on delicately flavored foods. Used sparingly, it adds explosive richness to eggs and omelets, and brings out the shy, retiring flavors of such garden gifts as fava beans and nasturtium or zucchini flowers. A few drops sprinkled over soft, nutty greens, with a light dressing of subtly flavored olive oil, is heavenly. Add a few ripe pear slices and it’s better still.

A great old Balsamico with foie gras is ambrosial. It’s exciting over chicken, pork or beef and can even hold its own with sausage. One prized Modenese recipe is to drizzle Balsamico over freshly cut slices of bollito misto.

While Balsamico begs for experimentation, we can be grateful for the publication of Pamela Sheldon Johns’ Balsamico! Among her seductive recipes—all featuring Balsamico—are risotto with roasted chicken and fennel, porcini crepes with Balsamico goat cheese, Balsamico-marinated rabbit, grilled trout with fresh grape and Balsamico sauce, creamy Balsamico potatoes, vegetable frittata, and ricotta cheesecake with orange flower water and Balsamico.

Not only one of the richest and most complex gifts of nature, Balsamico can be savored in an infinite variety of ways.

Because of the many “Balsamic vinegars” on the market, it can be confusing even for food professionals to know what they are buying. While there are some very good Balsamics made outside of the consorzios of Modena and Reggio Emilia, by far the best guarantee of age and authenticity is to buy a Balsamico Tradizionale from one of these two groups.

Some of the Reggio-Emilia Balsamicos can be marvelous, but our favorites have generally been from the Modena Consorzio. You know you’re getting Balsamico Tradizionale from Modena if it comes in the distinctive 100 ml Giorgetto Giugiaro bottle (see Production, above).

Each Balsamico Tradizionale from Modena falls into one of two categories: 12-year-old (also known as “Traditional”) or 25-years-old (also known as “Extravecchia”). These ages are minimums, however. Twelve-year-old vinegars may have 15 to 20 years of age, while the extravecchias can be 40, 50 or even 100 years old.

| Year | Description | Size | Notes | Avail/ Limit |

Price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Venerable Balsamic Set: 1 ea. Extravecchio 25yr, Mulberry 25yr, Oak 25yr 100 mL | 100 mL | 3 | $425.00 | add | |

|

Balsamic 12-yr-old Set: 1 ea. Cherry, Chestnut, Mulberry 100 mL | 100 mL | 3 | $245.00 | add | |

NV

NV

|

NV Cristo Selezione Paradiso 100 mL | 100 mL | 2 | $375.00 | add | |

NV

NV

|

NV Cristo Selezione Amelia 100 mL | 100 mL | 2 | $325.00 | add | |

NV

NV

|

NV Balsamico Blown Glass Stopper-Pourer | 12 | $9.95 | add |

New discoveries, rare bottles of extraordinary provenance, limited time offers delivered to your inbox weekly. Be the first to know.

Please Wait

Adding to Cart.

...Loading...

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.