Which site would you like to visit?

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.

“We dream of making the best Rioja wine of the 18th century.”

These are the intriguing words with which Telmo Rodríguez introduces his Rioja Alavesa estate, Bodega Lanzaga. Telmo’s statement is provocative, and it’s intended to be.

Telmo has been the most prominent voice for having Rioja’s greatest terroirs recognized and for returning to small-scale, traditional winemaking to most clearly express their characters. But his voice has been heard far beyond his home region. He was the prime mover behind the Terroir Manifesto, the landmark 2015 document that called on all of Spain’s appellation regulatory bodies to finally “approach a classification of the land in terms of quality.”

Telmo is not just an outspoken champion for quality. As a winemaker, he is leading the small brigade of terroir-focused Rioja growers whose influences is being felt throughout the region. And he has led not only by word, but by example. His Bodega Lanzaga represents a unique array of superior terroirs, many with old vines restored by him and his team. And the wines he’s making from them are among the most acclaimed Spanish wines of our time.

In a 2016 interview for Canada’s National Post, Telmo told journalist John Szabo that his goal is to “bring back to life the real traditional taste of Rioja.” But the traditional taste he was referring is not what we think of as traditional Rioja. It’s what existed even earlier, when a multitude of small cosecheros, working from tiny local cellars, created individual expressions the region’s vast diversity of terroirs.

Today, Telmo uses many of the same methods, both in the vineyard and cellar, to craft authentic wines from old vines grown on the lower slopes of the Sierra Cantabria mountains in Rioja Alavesa. But the wines don’t just evoke Rioja’s past. They are among the most compelling wines being made in Rioja today. This is particularly true of the top cuvées, which consistently earn 96 to perfect 100 ratings from Luis Gutiérrez and Tim Atkin, the two most prominent contemporary critics of Spanish wine.

When Telmo founded Bodega Lanzaga in 1998, it was a return to his home region, the Basque Country of which Rioja Alavesa is a part. Born in the city of Irun, he grew up there and at the ancient Alavesa estate of Remelluri, which his father Jaime Rodriguez had purchased in 1967.

Jaime was a provocative figure in his own right, releasing an all estate-grown Rioja from naturally tended vines in the 1971 vintage, a sharp departure from the dominant practices of the region’s large bodegas, which at that time emphasized brand names over terroir.

Telmo studied winemaking at the University of Bordeaux, and interned at several prestigious châteaux, including Cos d’Estournel. But he felt far more at home in southern France, working with smaller growers who were much closer to their land.

His time with Trévallon’s Eloi Dürrbach and Gérard Chave in Hermitage were formative experiences. As as he told Szabo, “they were heroes of the vineyard, willing to work in dramatically difficult vineyards at a time when their wine prices could hardly justify the effort.”

At Jaime’s request, Telmo returned to run Remelluri, but his vision was different from his father’s. He saw Spain’s abandoned ancient vineyards, including those once cultivated by Alavesa’s small growers, and he sensed the potential for greatness. With his friend Pablo Eguzkiza, he started Compañia de Vinos Telmo Rodríguez, and between 1994 and 1998 they embarked on a journey to discover and make wine from great old vineyards throughout Spain.

Having learned winemaking in Bordeaux, that experience drastically altered Telmo’s view of how wine can and should be made. “Our travels have brought us into contact with our ancestral and unknown viticulture full of character and experience … it’s been an emotional experience reliving how our ancestors worked the land … we have learned how they used endless combinations of different varieties to adapt to the diversity of the land and climate.”

In 1998, Telmo’s journey brought him back to Rioja, where he chose the distinctive landscape and climate of Lanciego in Álava (Rioja Alavesa) for his wine “de pueblo.” If he were going to make wine in Rioja, it would have to be from a specific place, a village (pueblo) with great terroir and a long history of viticulture.

But that was easier said than done. In 1998, it was illegal under Rioja appellation rules to label a wine with a village or vineyard name. For the very conservative regulatory authority, the Consejo Regulador, Rioja should be about brand names and classifying wines based on length of aging, rather than any consideration of origin. It took Telmo and other advocates for terroir nearly two decades to get the Consejo to finally allow even limited village and vineyard designations in 2017.

The labeling rules were not the only problem Telmo saw. When the great bodegas were established in the late 1800s, it largely ended the tradition of small growers making their own wines from individual cellars in each village. The idea that any winemaking culture had existed before the 1850s was lost.

The emergence of the great bodegas also shifted the focus to Rioja Alta, and especially the area around Haro. But in fact, prior to this period, Rioja Alavesa was arguably the most important wine-producing area of Rioja, with a noble tradition dating back to the late 1700s.

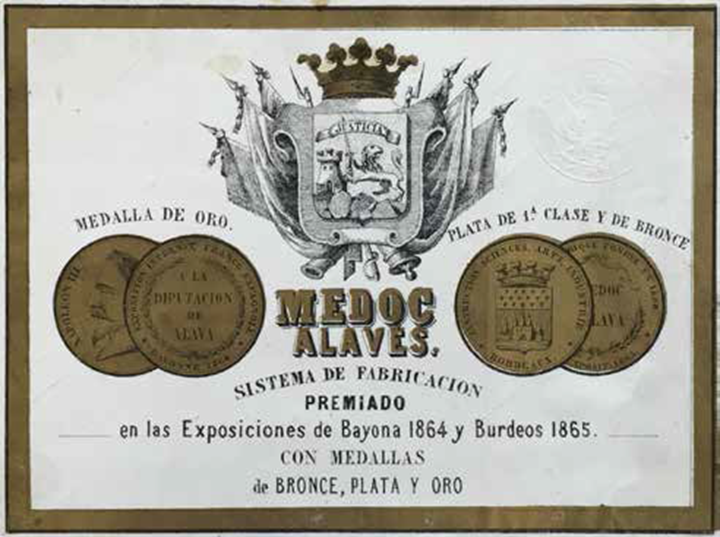

To bring this perspective to a wider audience, Telmo sponsored the publication of El Medoc Alavés, a wonderful history detailing the heritage that had previously existed in Alavesa. This was a time when farming and winemaking existed on a much smaller scale, expressing individual terroirs.

The genetic diversity of grapes was also far greater. Beyond the varieties of Tempranillo, Garnacha, Graciano, Viura and Mazuela we know today, up to fifty different red and white varieties were densely planted as field blends, producing highly complex, complete wines.

Telmo embraced these older traditions to again let Rioja’s complex landscape speak.

Telmo continues to lobby for more intelligent rules regarding labeling, calling for a Burgundian-style classification of Rioja, from regional to village to single vineyards, so that the world can know the qualities of the region’s diverse terroirs.

But while such a classification is probably years in the future, Telmo has made his Bodega Lanzaga one of the most prominent examples of terroir-based winemaking in Rioja.

Whether village- or vineyard-based, all of his Lanzaga wines are pure, field-blend expressions of Alavesa terroirs, made by the early methods he and Pablo have studied and championed.

Each terroir is organically farmed, and in the cellar, all fermentations take place with the native yeasts that have populated the region for a millennium. The winemaking is as simple and natural as possible; the fermentations take place in concrete tank for the village wines and open wooden vats for the single-vineyard cuvées.

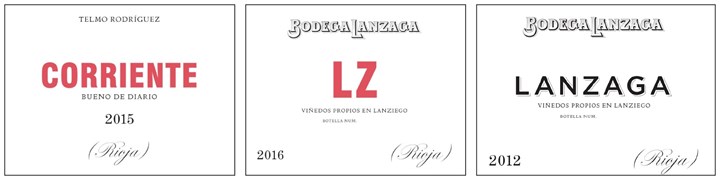

The Lanzaga range begins with three village wines. The first is Corriente, a tribute to the traditional type of everyday wine made by the Alavesa’s early twentieth century cosecheros. Sourced from the expertly farmed vineyards of their fellow Lanciego growers, it is a deliciously approachable wine representing the village’s ancient wine culture.

Next up, is LZ, which is derived from six of the estate’s own organically grown vineyards. The grapes are Tempranillo, Graciano and Garnacha fermented and aged 6 to 7 months in concrete. This, too, is made to recapture the quality and character of young, approachable wine as made by Lanciego’s growers in the past.

The top village wine is Lanzaga, the estate’s flagship and a pure expression of Telmo and Pablo’s two decades of work in Lanciego. It is a selection of the best fruit from five exceptional parcels, located on both limestone slopes and sandstone plateaus at 450- to 650-meters elevation. As such, Lanzaga represents all of the following values: “respect of the place, bush pruning, field blend, organic viticulture, concrete fermentation, aging in foudres and barrels of different sizes and origins, keeping always a limited production of human size.” It is, in short, a beautiful representation of its village, as was made prior to the Bordelais’ arrival in the mid- to late-1800s.

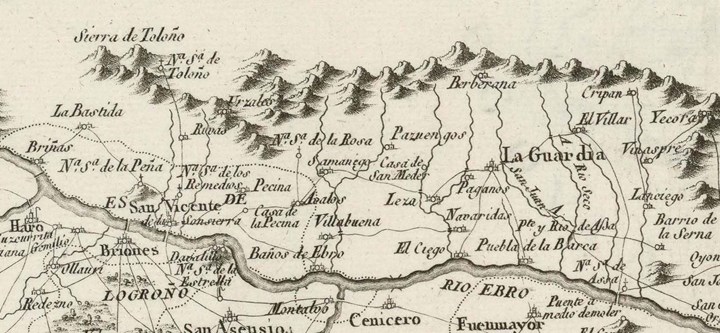

1804 map of Rioja Alavesa, from La Bastida in the west to Lanciego in the east

For their acclaimed single-vineyard bottlings, Telmo and Pablo have assembled four extraordinary old-vine sites.

The first is La Estrada is a .64 hectare plot at the highest point in Lanciego, a 610-meter slope of poor calcareous clay. From its Tempranillo and Graciano vines planted in the 1940s, the La Estrada site produces a Rioja of bright elegance and harmony, owing to the site’s northeast-facing exposure.

El Velado is a warmer site, lying at 600-meters altitude in the eastern part of Lanciego, a very chalky parcel of 80-year-old Garnacha and Tempranillo vines, augmented with other ancient local varieties, including some white grapes. Oriented to the west and south, El Velado’s wine is rich, spicy and complex, and a fascinating counterpart to La Estrada’s elegance.

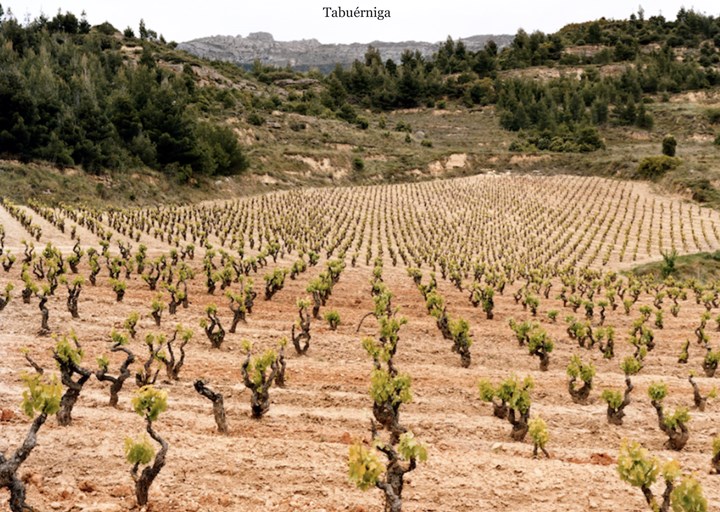

Last, but certainly not least, are the two single-vineyard wines from the historic village of Labastida, where grapes for wine production have been grown for at least 1300 years. Tabuérniga is an extraordinary vineyard that Telmo became aware of while at Remelluri in the late 1980s. A narrow, steep valley opening to the southeast, with a great diversity of very old bush vines are planted on terraces of poor, silty chalk-clay.

Tabuérniga is a magnificent Rioja of great aromatic complexity, and a palate that magically balances richness with finesse. Along with Las Beatas, it is one of the truly elite terroir-based wines being made in Rioja today.

The crown jewel in the Lanzaga array is Las Beatas, a steep, northwest-facing slope of cold, sandy soil divided into eight terrace levels that date back to the 7th century. Telmo and Pablo spent fifteen years restoring the vineyard before making any wine from it. The 1.9 hectares under vine consist of a very old, complex field blend, with the newly restored terraces planted with massale selections from the original vines.

At 5000 vines per hectare the vineyard is, according to the Rioja Consejo Regulador, technically illegal. But Telmo was able to persuade them to accord Las Beatas experimental vineyard status. As he told Szabo: “Imagine, a thousand-year-old vineyard planted more or less as it was back then, considered experimental!”

Las Beatas is a true Rioja grand cru, a complete wine of kaleidoscopic complexity, weightless intensity, and incredible finesse. Above all, it has those extra dimensions found only in wines from the greatest terroirs.

Sadly, the 125 cases of Las Beatas produced is only slightly more than 165 cases made of Tabuérniga. Consequently, few Spanish wine lovers will ever have the chance to experience either wine. But if you do have the opportunity, don’t let it pass you by.

New discoveries, rare bottles of extraordinary provenance, limited time offers delivered to your inbox weekly. Be the first to know.

Please Wait

Adding to Cart.

...Loading...

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.